ESG Definitions

Download the document: Second Edition - POST-CRISIS ESG: from a “Ptolemaic” approach to a “Copernican” vision. For further documents go to the rating page.

Definitions adopted by Standard Ethics

- Sustainability

- Responsibility

- Sustainability rating

Why these definitions

- ESG measurement

- Measuring Responsibility

- Measuring Sustainability

Definition of Sustainability

Sustainable Development policies are about the generations of the future; they have taken on a global dimension; and they are implemented on a voluntary basis. It is up to the main supranational organisations, officially recognised by nations across the globe, to establish the definitions, guidelines and ESG strategies related to sustainable development through science.

Economic entities pursue – to the extent deemed possible – aims, strategies and guidelines on Sustainability, they do not define them.

Definition of Responsibility

It is a voluntary ESG action or strategy, defined by the company or investor implementing it. It may be based on valuable ethical choices arising from dialogues with stakeholders. It may not be sustainable and therefore not aligned with international guidelines.

“Responsibility” is not a rateable notion.

Definition of a Sustainability Rating

Measuring the Sustainability of economic entities means providing comparable and third-party data on their overall compliance with international guidelines.

Why these definitions

While it is clearly necessary to adequately define the conceptual notion of Sustainability, it is also necessary to distinguish it from Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) which are similar notions. A distinction that Standard Ethics has deemed necessary to make before developing its own methodology, since it believes that choosing one approach over the other will result in significant operational differences. Since the Seventies, the fascination with "extra-economic" values and "intangibles" (the so-called ESG policies) has taken root in economics, but – in practice – this has led to the adoption of two alternative approaches that have never been properly differentiated:

- on the one hand, the corporate dimension where non-financial investment in the ESG area had to be consistent with the Company's development: Corporate Social Responsibility and Socially Responsible Investments;

- on the other, a systemic approach, where the focus was on the general interest: Sustainability.

In other words, in the first case, the centre of the orbital system is the Company: this is where the observation begins and the "interested parties" rotate around it, in the case of both a productive enterprise (CSR) or an asset management company (SRI).

In both cases, what is emphasised is, on the one hand, the central role of the Company (or investor) and, on the other, that it is free to decide what "responsible" contribution it chooses to make to social and environmental matters. A "micro-economic" vision which is strongly based on the Stakeholder Theory of the American sociologist Robert Edward Freeman (1984). In the publication of his "Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach", CSR emerged as a coherent and functional solution.

According to Standard Ethics, this is a "Ptolemaic" model, because both the stakeholders and those who implement the extra-economic and non-financial decisions feel that they are at the centre of the visible universe and thus determine the geography of the interests at stake.

Strategic ESG policies are defined from this perspective – and they may also include ethical, religious or other specific characteristics.

According to the Standard Ethics model (first developed in 2002), a systemic approach evolves with the first global, social and environmental emergencies, which were initially outlined within the "OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises," the outcome of multilateral negotiations published in 1976. However, this was an instrument that was still disconnected from a general framework and solid strategic guidelines. It was not until 1987, with the United Nations Report by the Brundtland Commission "Our Common Future," that the idea of Sustainability and Sustainable development was born: "A development that satisfies the needs of the present without compromising the capacity of future generations to satisfy their own".

A conceptually "Copernican" and systemic vision, since those who make "Sustainable" choices do not see themselves as being at the centre of the world. It is a vision that prevents those who undertake to implement voluntary extra-economic policies from being free to decide where they should invest their efforts. It is no longer the Company that defines the macro-strategies in the ESG area, but global decision-makers, those international organizations that have been delegated by national States (and ultimately by their citizens) to draw up global policies in the interest of humanity and future generations. The parties involved also acknowledge that the whole system is affected by variables that carry more weight than their own vested interests carry. What Standard Ethics proposes is a more accurate classification that takes into account both these rationales.

The distinction between Sustainability on the one hand, and Corporate Social Responsibility or Socially Responsible Investment on the other, leads to four conclusions which are analysed in depth in the following document: Second Edition - POST-CRISIS ESG: from a “Ptolemaic” approach to a “Copernican” vision.

- the cases of Companies adopting Corporate Social Responsibility, or financial products based on Socially Responsible Investments (and related ethical approaches), are not comparable by means of scientific criteria, and are therefore "falsifiable";

- the methodologies implemented in an attempt to provide measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility and Socially Responsible Investment cases are based on "cluster" measurements. They are not holistic methodologies, suitable for developing Sustainability ratings;

- Corporate Social Responsibility policies and Socially Responsible Investments present some significant implementation limits, the main one being the fact that they are undertaken only if they are economically justified for the entity that is implementing them;

- consulting activities for investors, created to measure cases of Corporate Social Responsibility and Socially Responsible Investments, are not business models that are coherent with the issuing of ESG ratings.

ESG Measurement

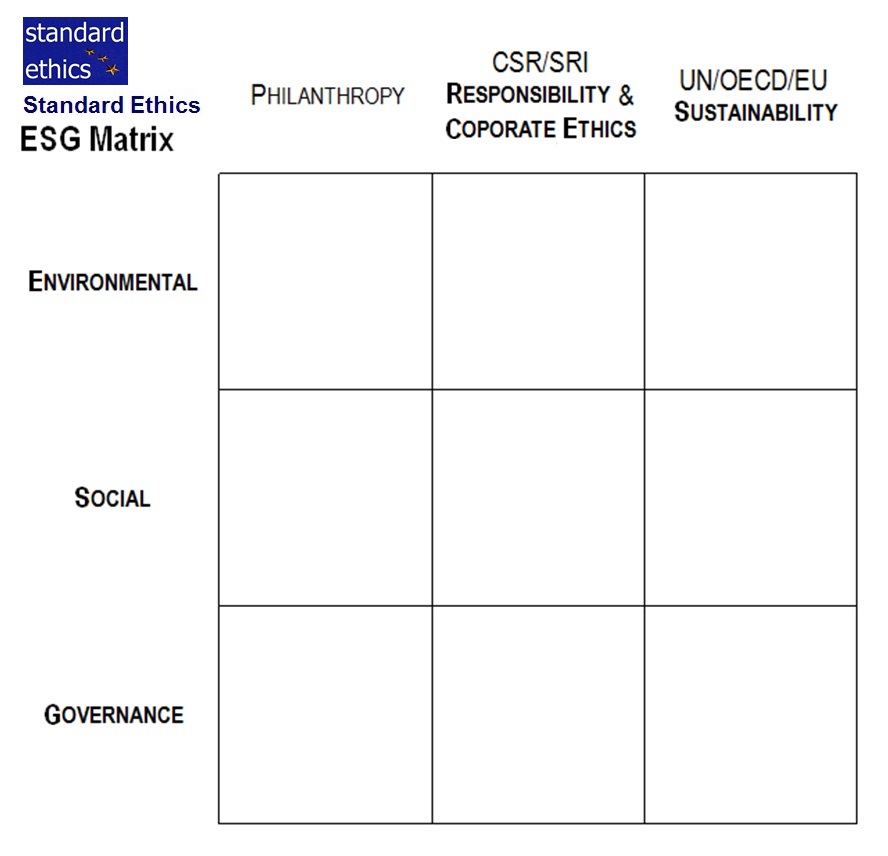

Every single area of the ESG universe can be observed and measured through three approaches that Standard Ethics summarizes in a matrix. Each measurement can be made using qualitative or quantitative methods.

The governance, environmental or social aspects are evaluated in coherence with the three approaches mentioned above, and therefore they are based on different methodologies.

Measuring “Responsibility” and “the paradox of the evaluator”

According to best practices, a Company that wants to determine its own model of "Responsibility" should follow a well-defined methodology. This methodology (relating to Stakeholder Theory) requires the model to be determined by the Company itself. For the purposes of ESG policies, the economic entities that adopt CSR criteria can therefore be defined as a "whole" (from a scientific point of view) because they are considered to be members of a group that implements, more or less correctly, the same methodology. Using the term "comparability" (also according to any applicable scientific definition) it is clear that the only measure that can be correctly used among the components of the "whole" is the measure that refers to the quality of the methodology implemented by the individuals therein.

After this, any evaluator will inevitably be faced with a multitude of ESG choices and policies. Any Company (even in its role as investor) can identify its own legitimate process and its own model of "Responsibility". If so, it will offer its own representation through a Materiality Matrix, and thereby illustrate the system of its corporate policies and its reporting practices.

It is, however, legitimate for an external observer to apply his or her own ethical-value model, as in the case of SRI investors, and equally to evaluate those implemented by others. In so doing, he or she can choose those which are considered more closely aligned with his or her own vision.

Here we are entering into issues relating to free will and metaphysics. We have gone way beyond scientific measurement matters: falsifiable models and the principles of comparability.

The resulting conclusion is quite simple: CSR is not a system designed to be measurable: the individual models of Responsibility adopted by corporations are not comparable, but they can only be shared or agreed with, as is the case with any choice deriving from ethical or value-related considerations.

Nevertheless, although it is not possible to make a correct holistic comparison between the "Responsible" entities, it is possible to evaluate individual topics and themes.

Through quantitative assessments of data collected through questionnaires, individual topics (per KPI) can be measured, even if they are different and not homogeneous. Reporting systems, such as the GRI, break down the individual items covered by potential ESG actions, thus offering detailed and quantifiable criteria and areas.

External analysis is carried out for individual clusters and evaluations are homogeneous by topic, also thanks to possible taxonomies. Each cluster offers quantitative data and median values (by sector, size, geographical affiliation, etc.) on which to evaluate individual performances.

Several medians can be combined in order to provide an overall picture. But comparability remains complex: the sum of relative measures does not, in itself, provide a holistic comparable measure.

In any case, you cannot exceed the limits established by the very nature of CSR, which is based on the free definition of its objectives: in the absence of a benchmark valid for all companies or all ESG funds, in the absence of a single roadmap for all, a great mathematician like Bruno De Finetti would have said that the analysis of detail is accurate, but tells us nothing.

But the lack of a possible full comparability between "Responsible" entities is not a problem within CSR, because the objective is not to develop a rating model.

In the case of SRI investors, those who use the information are in fact applying arbitrary choices in relation to their individual investment objectives. The service they need from their consultant or ESG Data Provider is a tailor-made service, one that can be customized to their needs and objectives. Cluster data is useful for this purpose. The Asset Management Company will decide which data to consider and to what extent. And this could give us the case of a sovereign fund that decides to exclude the "Oil" sector, and focus on renewables or gender equality to create its own ESG portfolio, without considering other data.

The paradox of "Responsibility"-based ESG measurements, as described here, ultimately says much more about the evaluator's strategy than about the strategy of the Companies under observation.

Measuring Sustainability

The determination of a single fixed point makes a holistic, homogeneous – and ethically neutral – comparison possible. This condition makes it possible to compare the distance that separates two entities with respect to a shared strategy or to pre-established and unambiguous quantitative targets.

It is also possible to develop analysis grids and standard algorithms that make the measurement objective and falsifiable (in the sense Popper gave the term).

If we consider the players implementing ESG Sustainability policies as planets orbiting around a single gravitational centre, then the rating measures the distance between them and that centre.

As there is only one port of call, the quality of the routes taken by the individual vessels takes on a measurable value and the distances can be used for scientific purposes. The speed at which the vessels approach the port of call also appears to be a calculable and shared variable.

Here, then, the criterion according to which the value of the single clusters is established changes: it can no longer be a criterion related to the worldview of the entity implementing Sustainability (or judging it), for the cross-section of the clusters is established based on objectives decided at a global level. Further, the data generated by the analyses become part of a major mathematical function. Under these conditions, and only under these conditions, everything can be integrated into a standard algorithm.

If, for the sake of simplicity, the United Nations were to establish alcohol consumption as an organic element of the notion of 'Sustainable development', then the data would become relevant and would make sense if we were to compare the Sustainability of George Best's lifestyle with that of an orthodox Mormon. And, in relation to international indications on the climate emergency, the "cluster" of luxury cars also makes sense and should be measured, albeit in relation to their use and emissions. On the other hand, the number of George Best's amorous adventures with women (of age and consenting) not being at the top of UN, OECD or EU's thoughts on Sustainable development, would seem irrelevant, with all due respect to the Mormon's peace of mind and his admirable morality.

The ESG metric of the "Sustainability" assessment is therefore profoundly different from that used in the "Responsibility" assessment (CSR/SRI) because the areas of interest, the weight of the factors, the objectives to be achieved, are all part of a single algorithm.

In the case of "Sustainability" it makes no sense to endeavour to provide your client with as many data as possible and then let him or her start a decision-making process based on his or her point of view.

“Sustainability" predefines the targets and policies to be implemented, so that the data are selected and weighted according to unambiguous indications and priorities. They become analysis targets for all entities observed. Therefore, the quality of the analysis does not lie only in the ability to obtain and measure data, but above all in the ability to interpret data and give it an efficient ranking according to clearly defined criteria.

The decision on what to observe, and what not, in order to obtain a comparable and credible form of judgement is crucial.

In the case of Standard Ethics, the decision was to concentrate on five macro variables, identified and made public in 2002, implemented by Standard Ethics starting in 2004.

These variables -- which have remained unchanged -- have characterized the agency's proprietary algorithm since then.

The final numerical value, that is attributed to each single variable allowing the algorithm to perform, comes from a series of analyses based on some "markers". The decision to call these analysis elements "markers" comes from the desire to highlight how they have the function of revealing the nature of the entity under rating, with the lowest possible approximation of error. Therefore, it is not a question of measuring impact through unrelated purely quantitative data, but rather of assessing the entity’s structural and strategic adequacy on the basis of the principles of "Sustainability" (as interpreted by an external reviewer).

Modern science distinguishes the field of data collection and measurement from the field of those whose task it is to interpret them, to provide opinions and suggest theoretical hypotheses. In fact, the rating is provided by the latter: the client does not commission the analysis to be provided with numbers, but rather to receive an interpretation and an opinion. A third-party opinion on where the entity could be positioned if it were placed on the map showing the boundaries of "Sustainability". An opinion which, as we have seen, has the “market” as its end user.

What should or could a non-financial Sustainability rating be?

If ESG non-financial ratings were categorized, and semantically qualified as a "Sustainability ratings," they would and could be similar to a credit rating: a third-party opinion - not by investors - based on a standardised analyst-driven process and a validated proprietary algorithm, that measures the distance between the issuer and the sustainability indications from major international organizations.

A notion, therefore, based on a few basic assumptions:

- the applicant for the rating is the entity itself under assessment;

- the subject of the rating may be its own bond issue or the entity itself (equity rating);

- the end users of the rating are the market and all investors;

- the disclosure of each "action" is also regulated by taking into account information asymmetries;

- the business model is consistent with the service of issuing ratings;

- the rating is based on a standard measure, validated on an absolute basis